Everything changes … nothing changes. I’m back on my bicycle — the same one that almost a year ago carried me from Portland to Utah — but this time doing a sort of tour of my quasi-native turf in British Columbia. Long with my friends Josh and Mark, we’ll make a two-day trip up the east coast of Vancouver Island between Victoria and Nanaimo, and then after a

Author: Matt Perry

On getting lost

I once heard about a botanist in Hawaii with a knack for finding new species by getting lost in the jungle, by going beyond what he knew and how he knew, by letting experience be larger than his knowledge, by choosing reality rather than the plan.

– Rebecca Solnit

Salt Lake City

Holy crows! I’ve made it to Salt Lake City. Here’s the view I saw when I rounded the corner from the area west of Bountiful as I began to follow the course of the Jordan river into the city.

The sun was starting to get low (you can see the long shadows on the road) and the swampy and scrubby land all around became golden in that light. It had been a hard day, and I felt a sudden sense of relief and catharsis to be able to finally see the end of my journey (almost) rising up ahead. I let out a big whoooooop, which I’m pretty sure that no one could hear, but I’m fine with the idea that someone did. At this point everyone thinks I’m insane anyway.

The day had been hard. It wasn’t the most physically demanding of the trip (that would have to be the ride from Prairie City to Vale in Oregon) but it wasn’t too far off in terms of how I felt at the end. The milage was slightly on the long side, but not too bad — a respectable 85 miles. And there was one mountain pass. I had to ascend out of Logan, Utah and over the north end of the Wasatch back down into the Salt Lake basin. This pass was made worse by the altitude since at well over 6,000 feet it was my highest climb yet, even though the total gain involved was under 2,000 feet. Despite having been above 4500 feet for a while now, It’s pretty hard to climb up there, and the sun is extremely harsh. I’m trying to be very careful about sun exposure right now — I’d managed to badly sunburn my lower lip earlier in the trip and it has remained an irritated mess (and caused other mouth problems.) I’ve amassed a collection of several ointments to deal with the issue, but none seem to be working that well.

There were other small annoyances today which added to the slog. For the first 40 miles, traffic was a real problem. Though US 89 over the mountains had nice wide interstate-style shoulders, those immediately disappeared in Box Elder County south of Brigham City. There were a few sketchy parts with no shoulder before I got on a suitable road, and I’m glad I was clear-headed and experienced enough to handle them. For the last 50 miles or so, the wind was a real bummer. It blew in my face at about 10-15 miles/hour, cutting my speed by about 2-3 mph and adding a lot of effort to every mile. In the few places where the road was sheltered from sun and wind giant clouds of gnats lurked. These stuck to my clothes, arms and glasses in a thickening matte which I soon gave up trying to scrape off.

On the other hand, there were good moments too. For the last 30 miles into the city I was away from traffic entirely on a great deserted bike trail. Thanks Salt Lake City! And I saw the most beautiful formation of migrating geese descend in a glorious chevron over the Mantua Reservoir as I sped down the backside of the mountain pass I’d just climbed. But by the time I rolled into SLC I was pretty burned out, and ready for a break and a sushi burrito with my friend Rachel. Today is all about sleeping and catching up on a bit of work. Tomorrow I’ll load up the bike one final time for the 35 mile ride up the hill to Park City, where I’ll spend a week with my co-workers. Maybe I’ll post some kind of summary at some point, but for now I’m going to get busy resting.

the lake bottom

I was back in the saddle today after a day off in the enclave of Lava Hot Springs, Idaho (population ~400.) I can’t recommend this place and its perfectly crystalline hot pools enough. Go there! If you do, you’ll also understand where all of the hippies in south eastern Idaho went — those that didn’t leave entirely.

The ride out of town and back down into the broad valley of the Pontneuf river was a joy — I was rolling swiftly and made great time in the morning under a non-threatening cloudy sky that more than anything kept the harsh sun away. It was an amusement to watch the shifting patterns of clouds above me; now dark, now lighter, now entirely blue. What part of the shift was due to the clouds, and what was due to me, inching my way along at a respectable 14.5 mph? Aside from a few temporary headwinds, I made great time, and was soon pointed directly south at Preston, Idaho, a scrubby town less than ten miles from the Utah line (and, incidentally, the setting for the movie Napoleon Dynamite.) So I knew where I was going … but what I wasn’t prepared for the drama and tragedy the next sixty miles of this valley would reveal.

From the north, you can’t see Red Rock until your almost on top of it. It’s a pockmarked, gnarly looking butte to the right of US91, a mere point of minor geological interest, I thought, until I reached a small installation with some geological information from the always-helpful Idaho Historical Society. What I learned from their rustic sign was that this rock formation and the gap in which it sits was the outlet to a vast inland lake — a sea almost — which extended from this point in the north down the broad valley in front of me through the Salt Lake basin and all the way down far far into Nevada. In fact, the current Great Salt Lake (shrinking still) is but a remnant of this truly massive body of water which dominated the entire region until about 8,000 years ago when it began to recede and disappear due to a drying of the climate. Right under Red Rock flowed a rushing river with the volume of the Amazon which helped to drain the lake. Eventually it drained it totally — and the lakebed was now a desert, or a marsh, or in places a pasture. But scanning to the south, I could almost see its ancient contours marked on the hills and mountains all around — a broad, flat-bottomed valley which was the lake’s old bottom. And the high mountains, re-encroaching on my journey for the first time in a week — these would have been made islands or isthmuses by the expansive waters.

In deep time, no one owns the earth. It sweeps away the living and the dead. Seas rise and fall, climates change, entire ecosystems collapse or are birthed. This is a source of fascination for me, and of comfort. Because it seems so often that in the short term we do our best to dominate the land, to steal it and its products and to water our crops with the blood of other people. And so it was in this valley.

The first to inhabit the old lake-bottom were the western Shoshone people. This was their traditional hunting ground, used for thousands of years in as part of their annual hunting and gathering cycle. The next were the Mormons under Brigham Young, who by that time had established Salt Lake City and whose settlers had pushed up the Cache valley into this area. Then came other American pioneers — those who followed the Oregon and California trails and either homesteaded or exploited this land on their way through, and also gold miners who used the valley as a road and source of food. The land was getting crowded. The Mormons and other settlers began taking so much game (buffalo, elk, animals for fur) and land for cultivation that the Shoshone became impoverished and starved and were reduced to begging and sometimes stealing food from the newcomers. There were conflicts — real and invented, between all parties. The Mormons fought the US Government (there was a brief war even.) The Mormons then tricked and fought the Shoshone. The Shoshone, possessed of a keen sense of blood revenge, killed in the measure that they themselves were killed. The Mormons encouraged the Shoshone to steal from US wagon trains, and when they did the US responded without mercy. In the midst of the civil war Lincoln dispatched soldiers from California to crush the Shoshone’s non-existent “rebellion.” In January 1863, their main camp on the shores of the Bear River was attacked and harshly destroyed. Over 400 men, women and children were butchered and raped in the most ruthless fashion and their dwellings destroyed.

As I descended towards the bottom of the valley of the Bear, there were memorials from all sides. Native Americans commemorated the massacre by tying ribbons, yarn and other objects to certain trees. These flapped quietly and colorfully in the light breeze. Typically, we Americans erected a threatening-looking obelisk complete with shameful inscription: Erected 1932: the battle of Bear River was fought in this vicinity January 29 1863. Col. RE Connor, leading the 300 California Volunteers from Camp Douglas, Utah against Bannock and Shoshone Indians guilty of hostile attacks on emigrants and settlers engaged about 400 indians of whom 250 or 300 were killed or incapacitated including about 80 combatant women and children. 14 soldiers were killed, 4 officers and 48 wounded of whom 1 officer and 7 men died later. 72 were severely frozen. Chiefs Bear Hunter, Saowitch and Lehi were reportedly killed. 175 horses and much stolen property were recovered. 70 lodges were burned.

70 lodges burned. 80 “combatant” women and children. 250 or 300 killed (it was actually over 400.) In a way, it was a strange relief to see it all spelled out and counted like that, our government’s old and enduring cruelty to the original inhabitants of the land. Knowing exactly what happened, even if it’s presented in a twisted and near-celebratory context like this one, is at least in some way better than forgetting. I pedaled on, unable to think of anything else. I hope that monument stands for a long time and reminds us of what we as a country did at Bear River, and at so many other places across the west — of the cruelty and blood on which our mythical west is built, and on which we live and walk every day.

As the old lake-bed widened, I entered the state of Utah — center of American Mormonism. For some days, there’d been an LDS church in just about every little town I’d rolled through (Mormons are populous in southern Idaho too.) But now, the church was absolutely everywhere. Every single subdivision in Logan clustered around the spire of a Mormon church. Every single farming town had one too. I could see the grand temple of Logan from over 7 miles away, its twin spires pointing at the sky as if to say “Up there! Look away from this old lake bottom where so much blood has been spilled. Look at the sky and wonder about the clouds and ride your bicycle and don’t worry about it.”

It didn’t work. At the end of 81 miles I was still troubled by what I’d seen and learned. So I went to see a movie — the Martian, in which Matt Damon plays an astronaut trapped alone on Mars … a planet with no massacres, wars or nations. At least not yet.

ghost highway

I rolled out of Burley a bit later than intended due to a couple of work-related issues. Carrying my MacBook on my bike has made this trip possible, but it also makes work more accessible, though (as my team will no doubt attest) I haven’t exactly been spending hours each day reviewing code or resolving tickets. Once out of Burley, though, things seemed to happen fast. I cruised up to a nearby farming town, crossed the Snake river on a very old bridge, and then flew straight across land for nearly 25 miles, first through farmland and then into the desert.

I found myself on a ghost highway — a road that had been US30 in the days before the interstate came, but had since fallen into disuse and disrepair. It was a stunningly straight road, stretching out like a rail, daring anyone to find a kink in its course. The land itself was desolate, rolling gently away from me to a very distant line of hills grew up from the horizon. The only other people I saw for two hours were some hunters who’d pulled their white pickup about a quarter mile down a dirt side road toward the Snake. They were intermittently shooting at something — I could hear the snap snap snap of their small-calibre rifles. I quickened my pace, heart beating.

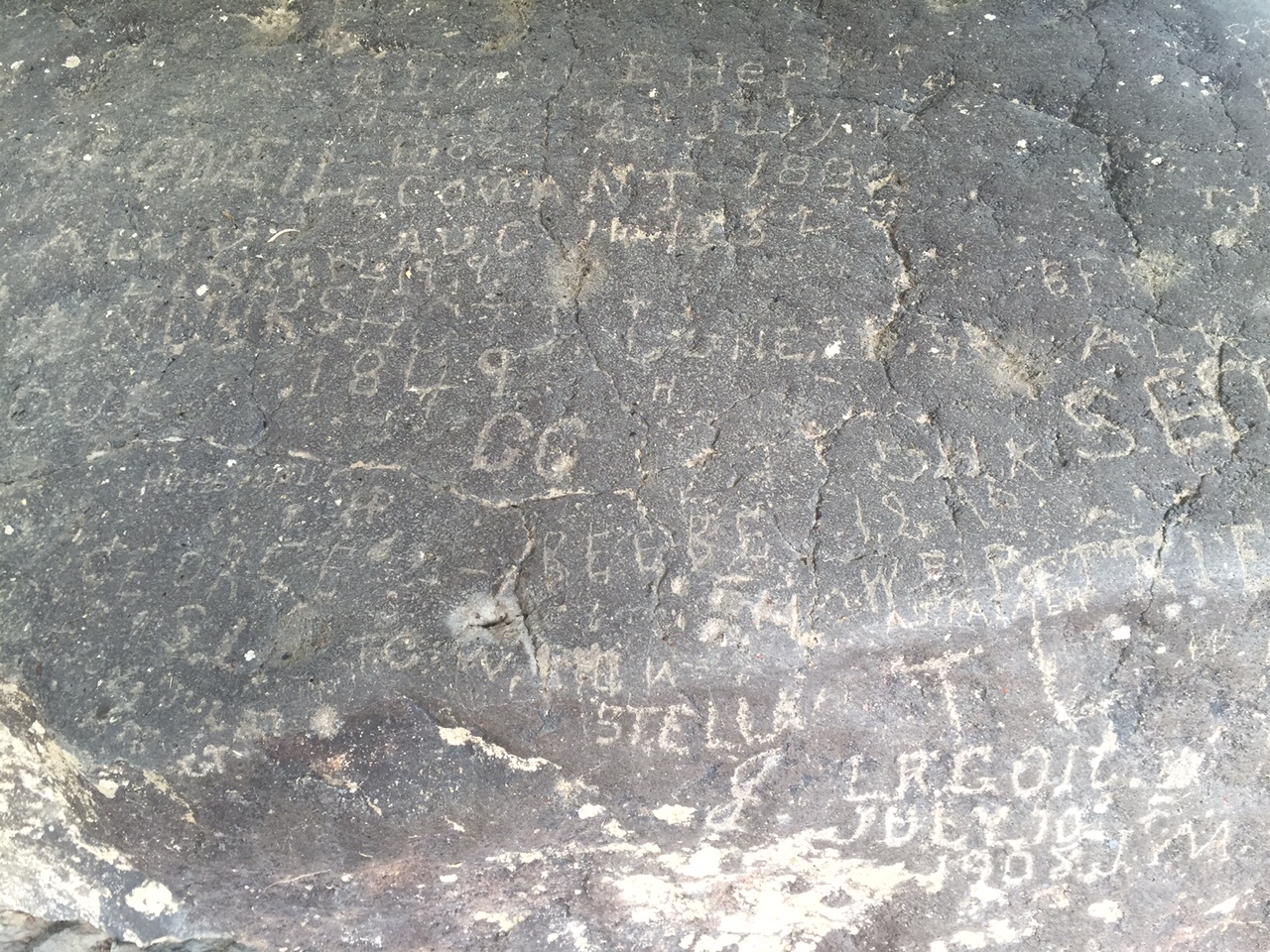

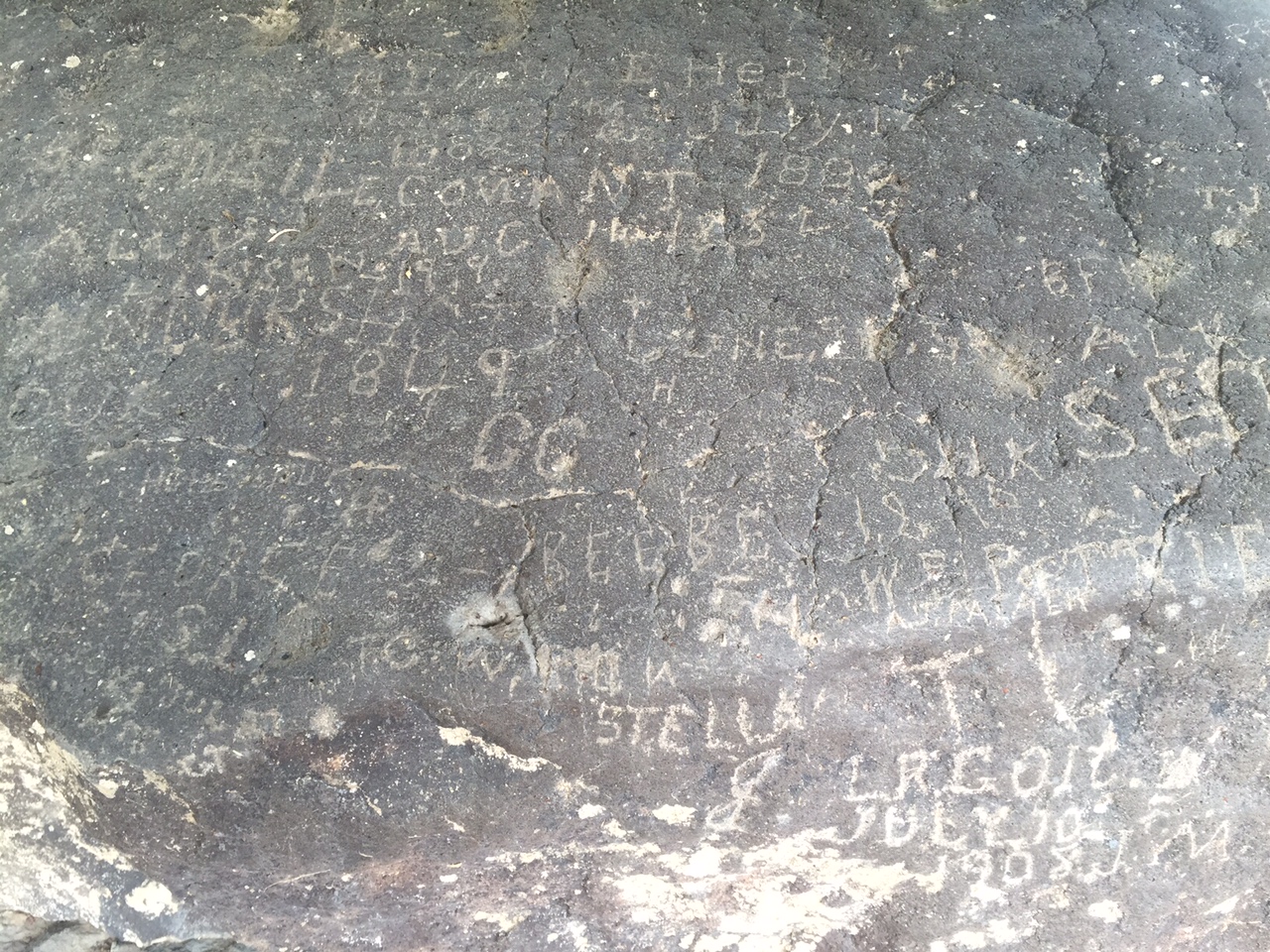

At around mile fifty, I passed Register Rock, a massive boulder in a sheltered hollow of land. The area around the rock was used in the old days as a camp for those on the Oregon and California trails. From the earliest times of the trail, it had been a practice to carve one’s name or initials in the rock, along with the date of passage … “1849 GC” “T Hepner July 19 1889” There were dozens or hundreds of inscriptions by those now long dead who came past this spot mostly on the way to Portland and the Willamette country. Others would follow California route, a branch that split south a scant 15 miles back (for me) or ahead (for them) of the rock, back where the ghost road re-joined the route of the interstate. This would have been the last campsite many on the trail would have had together before diverging — one imagines many sad partings.

I spent last night in Pocatello (a cool, high desert town with a slight methy tinge, but with a University and an excellent brewery) in the shadow of the Bannock range — a scrubby bunch of mountains that draws a 60 mile line down to the norther part of Utah from here. I’ll be in these mountains today, heading for the town of Lava Hot Springs, which I hope is as awesome a place as the name would lead one to believe. I’m going to rest there for a day — maybe even in a hot spring, before continuing south into Utah. See y’all in a couple days.

the apocalypse

Today was a day of roughly following the Snake river, and I84 (but neither too closely) as they both plunged headlong east. In about 50 more miles the river, but not the freeway, bends north toward its origin in the Tetons and Yellowstone National Park, but for now it heads directly east, through a gap between the low mountains of central Idaho to my north and the growing hills to my south. Today was also a day of vast fields of potatoes and sugar beets, of corn and hay and of farmers in huge vehicles working to get the crops in. The river feeds the land around here through a network of irrigation channels, many of which I crossed on little bridges on the secondary roads I took from Bliss down to Jerome, Idaho, north of Twin Falls. I decided to skirt this small city rather than enter it, and stayed deep in the farmland nearly all day, picking my way through the little agricultural towns that used to support the farming communities around them.

Many of these little towns are shells of their former selves — depressed little places with boarded-up buildings and only a few functional businesses and churches and perhaps a school or two. Farm families are more mobile than they used to be, and can drive the extra 15 minutes on the freeway to get to a WalMart or a chain supermarket rather than rely on the businesses that their forbearers likely patronized every day. Of course this change isn’t unique to this part of Idaho, but today I felt like I noticed it with particular sharpness as the haul of crops was brought in from the beet and potato fields all around me. At the same time, the only food on sale in any store was processed, packaged, or (maybe) fried — and all shipped in from far away. There was poverty too — the pretty obvious kind. Federal programs providing nutrition to pregnant women were advertised in every store window while Fox news blared loudly in the background. At one point a woman in her seventies with strange growths on both of her arms approached me as I was resting and asked me to help her son move a large couch. We moved it, he and I, into a falling-down house. His two daughters watched.

There’s something about rural America that blurs the lines of reality and fantasy and makes me doubt for just a second that there isn’t something … untoward … going on beneath the surface. At one point I turned a corner and was confronted by the biggest junkyard I’d ever seen — if a junkyard it even was. Dead cars, trucks, some of them very very old, stretched nearly to the limits of my sight. It was as if an entire section of someone’s farm had been surrendered to them and become a massive automotive graveyard. Maybe this air of unreality has to do with the fact that so many people here (and elsewhere in red America) believe, in quite a matter-of-fact way, certain things that are for me difficult to even imagine. “What is happening in our world lately?” demanded a placard at one gas station picturing a blood-red sunset with threatening clouds. “Join us Wednesday nights at Valley Christian Center, 35 Main Street Hazelton at 6pm, to find out. We will be taking a walk through the book of revelation with the series Agents of the Apocalypse”

If the world is going to end, then what isn’t possible?

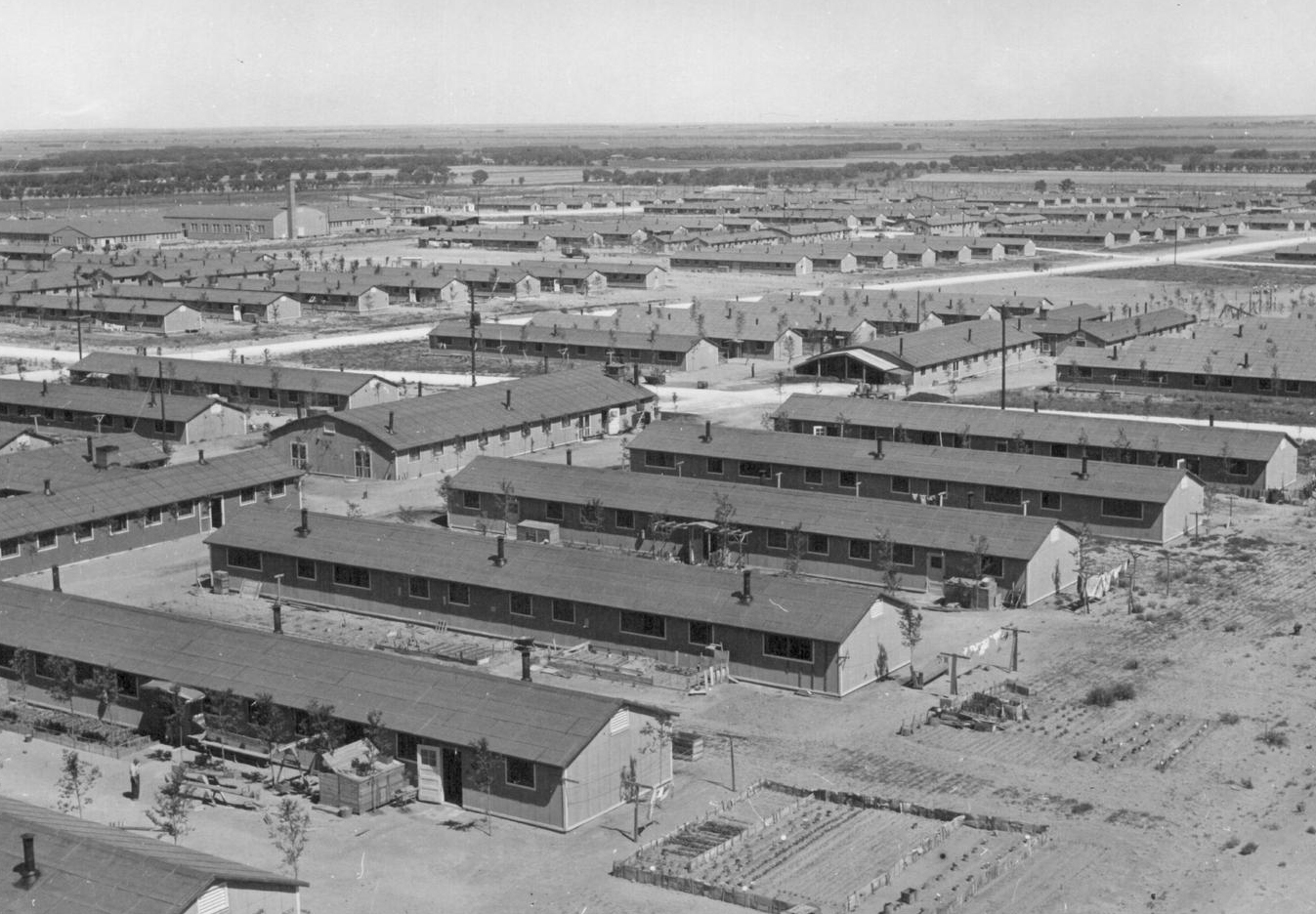

I’ve always thought that many Americans are possessed of a poor sense of when to pay attention to the past and when to look to the future. We quote the founding fathers when it suits us, but forget them as soon as it doesn’t. We commit obscene acts of genocide and crimes on a massive scale, and then forget that they ever happened. Half of us (or something) believe a supernatural apocalypse is coming, but we refuse to foresee the natural one we’re creating with our cars, coal plants and airplanes. I arrived at the turn-off for Hunt, Idaho at about 2pm under a hot sun. Hunt was the location of a concentration camp during the second world war which imprisoned over 9,000 entirely innocent American citizens of Japanese descent. The US government forced the sale of their property and businesses and then removed these Americans to places like this in the high desert for the duration of the conflict.

At the turnoff, a sign read: Excluded from their west coast homes by military authorities, over 9,000 Japanese Americans occupied Hunt Relocation camp 4 miles north of here between 1942 and 1945. Until they could resettle to other places, they lived in wartime tarpaper barracks in a dusty desert where they helped meet a local farm labor crisis, planting and harvesting crops. Finally, a 1945 Supreme Court decision held that United States citizens could no longer be held that way and their camp became Idaho’s largest ghost town. This sign (provided by the Idaho Historical Society) and its softball gloss of history are so offensively terrible that I won’t comment on them here, but the whole scene seemed only to add to the air of unreality — of denial and fantasy — that permeated this countryside.

Maybe I’ve been thinking dark and deep thoughts today because my rear end is really killing me — just a theory. Seven hours in the saddle is a lot, and I’ll be glad for another day off on Thursday, and a short day Wednesday. But as I drew close to Burley, my home for the night, I started pondering tomorrow and its challenges. It’ll be another longish one — today was 80 miles, tomorrow will be a few more even. And the route is a bit uncertain — all roads except I84 itself more or less fail about 50 miles to the east of here as the Snake enters a bit of a canyon, and it looks like I’ll be back on the freeway shoulder for about 6 miles tomorrow afternoon. But the day will end in Pocatello which is a pleasant-seeming college town. The day after tomorrow I will turn south and make for Utah and the end of the this voyage … assuming the apocalypse doesn’t happen first.

Bliss

I’m in Bliss … Idaho. Population 318. Today had it’s blissful moments, sure, but it was also a pain in the ass. For every wide open desert vista or unusual encounter, there was a slowly leaking tube (again!) or a spell on the interstate shoulder (one of only two I’ll need to endure during this trip.) So it was a mixed bag. But I’m here at the end of 96 miles feel and I feel strong and good.

I hadn’t originally planned to stop here in Bliss, but it was my stretch goal today, and I’m glad it worked out. The original plan was to overnight at Glenns Ferry about 20 miles back on the Snake River. But the fact that I’ve pushed on here makes a big difference in the coming days — it means that I can spend Tuesday night in Pocatello, Idaho (a town of some size and coolness) rather than American Falls (a town of neither.) It also turns Wednesday into a very short, pleasant day of only about 38 miles, with a hot spring at the end. After that, I’ll be taking Thursday off the road (some work, more hotspringing) and will hit Utah on Friday.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Today I rolled out of Boise to the southeast, staying off I84 for as long as possible. After a certain point, however, choices narrowed to a rough dirt track and the wide shoulder of the interstate. I endured the former for about 11 miles, and then it was back off at the “Boise Stage Stop” — a former hotel turned rest area and diner. The place was strange — there was some kind of dingy 24 hour mini movie theater, presumably for long-haul truckers who needed to stay off the road for a mandated number of hours. Sitting out front in the shade, I encountered my fist fellow-cyclist of this trip. Mark pushed his piled-high bicycle into the vestibule. According to him it was a cheap WallMart mountain bike that he’d modified. It was stuffed front and back with stuff he’d collected from his travels all over the west. Some of the stuff seemed plausibly useful, if a bit much: a spare wheel, many water bottles, clothing. The rest was a befuddlement: three large poles, a milk crate, a sign reading “pedaling for Christ.” A widower from Vancouver, Washington, Mark had taken to the road after losing his family somehow (I couldn’t make out how exactly.) He spoke very rapidly, almost rapid-fire. I did pick out that he was heading east (like me) though much slower I concluded, glancing again at his bike. I wished him well, and I meant it, though I also left him feeling as though there were more to his story.

From there it was back to the small roads, straight and seemingly without end. The desert flew by. There was no wind. I soon passed though Mountain Home, a military town, depressed and empty. The only things open were a Taco John’s, the payday loans place and a grocery store. A strange older fellow in a suit with a print tie of the words to the Lord’s Prayer asked if I worked at the Albertson’s we were standing in front of. He told me (some in Spanish, some English) that he’d moved here from Texas many years before and found the people of Mountain Home to be cold and unhelpful. “They’ll just leave you at the side of the road.” he said. He next asked me which I thought was wider, the Snake or the Rio Grande. “Lo siento,” I said, “yo no se.”

Wide or not, I pushed on towards the valley of the Snake. The land was green again now, irrigated and full of corn, beets, hay and onions. Nobody seemed to be around. The few I saw looked as though they were heading toward church or away from it, or maybe to the church of televised football. The fact was that I’d been lazy this morning and not rolled out of Boise until nearly 9:30 am. If I wanted to reach Bliss before dusk I had to keep going. At Glenns Ferry (a place where wagon trains used to cross the Snake on their way west) the shadows started to lengthen. What’s more, my rear tube started to leak again. Last time it was a thin filament of metal that had done the damage — possibly a radial fiber from a destroyed roadside tire. I have yet to find out the source of the annoyance this time (I’ll get out the tire irons as soon as I’m done writing this) … but I’m in Bliss now, and fed too at a horrible gas station diner that I pray does not make me sick. The motel room is okay though, and it only cost $38. In the morning I resolve to get going early and make for Burley and points east.