I’m laying on my bed here in the John Day country — in fact I’m in Dayville, Oregon (population 193) at the Fish House Inn, a comfortable country house converted into a little inn and RV park, all with a rather incongruous nautical theme. I just ate half a pizza with the owner Mike and his dog Zander, a giant golden retriever who chased our crusts across the lawn. The pizza was made next door at a roadhouse by a couple of guys who look like they might be veterans and/or hunters (at least if the amount of camo they wore was any indication.) The sign out front said “Espresso. Never forget.” The second sentiment surely relates to 9/11 or something right? I thought it unwise to reassure them that I could never. forget. espresso.

This beautiful country is the kind of place where you must allow things to happen to you. Eight miles back up the road I made my best decision of the day and turned off US 26 to visit the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. This monument protects one of the most important paleontological sites in North America — a swath of country rich in diverse biological history (it was a jungle, then a woodland, then a savannah, then a high desert, all in the last 40 million years) and volcanic activity (it was repeatedly and often suddenly buried in layers of ash and hot mud which flash-preserved entire ecosystems in stone.) Due to its age, there are no dinosaurs here. Rather, this place entombs layers of dead mammals: a medium-sized North American elephant, a tapir so large it looks like a rhino, a large-tusked pig, a giant bear/cat sort of thing whose branch on the tree of life evidently dead-ended. There is also a rich history of plants: bananas, tea trees, avocados, giant oaks, palm trees — all grew wild in eastern Oregon in the deep past.

While I was thinking about all of this in the excellent monument visitors center, I was approached by an affable dude named Jimi (“Like Hendrix”) who asked me all about my trip and where I was headed. It turns out that he and his son cycled throughout New Zealand last year — they immediately invited me to spend the night at their house when I passed through Prairie City, Oregon. I thanked them and told them I’d see them tomorrow. Sometimes good things just happen. What’s important and sometimes not so easy for me is to remain open to these signs of hospitality.

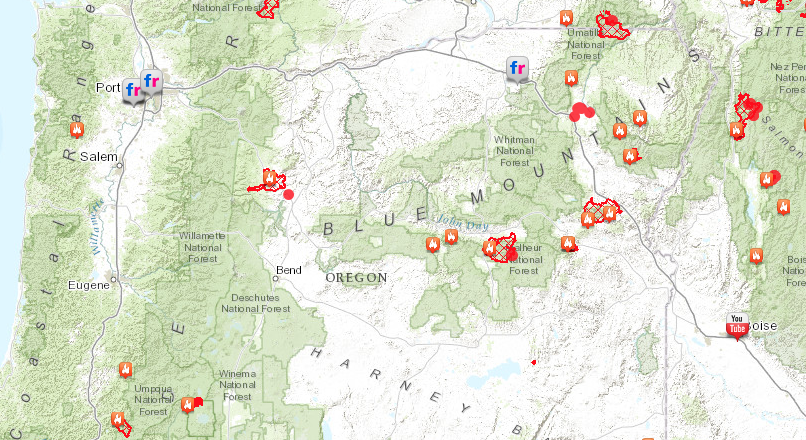

Maybe the uptick in human kindness has something to do with the harshness of the land though which I passed today. It’s as if the difficulty and directness of life in a place like this needs to be compensated by a greater sense of humanity. I first noticed this back in Mitchell, a tiny town which served as my lunch stop. Mitchell is a crusty speck of a place in the middle of a truly huge and forbidding wilderness. The only business open in town was a little cafe serving lunch to a small crowd of local people. “It’s taco Tuesday” I was told by a genuinely happy local, sitting at the bar. It was. I ate my large white-people taco with vigor. Outside, a barely functioning pickup truck pulled up with a tank in the bed which I soon detected was used for servicing rural septic tanks. Its driver was a sun-baked man who appeared to be in his seventies and spoke almost exactly like Yosemite Sam. He provided me an impromptu survey of the road ahead — especially the dangers of a stretch of road about 30 miles down where US 26 enters a deep canyon and visibility is limited. I thanked him for the info, he seemed genuinely concerned for me, which felt good. As it turned out the canyon in question was definitely a place for caution, but far worse (and totally unmentioned by the rustic gentleman) was the truly hellish climb out of town. Known locally as the “Mitchell grade” it’s an eight-mile, 2500 foot climb out of the deep canyon in which the little town sits. I climbed it in the intense sun, the taco dancing uneasily in my stomach. I had to stop four times in what shade I could find under the scrawny pines to chug water and catch my breath. At one stop I happened across a rather ominous (and perhaps politically dubious) historical marker, some five miles and a good 1500 feet above Mitchell. It read: W. W. Wheeler. For whom Wheeler County was named. First President of East Oregon Pioneer Assn. Also US Mail carrier from The Dalles to Canyon City. Was attacked near this spot by Indians. Was wounded, mail looted and coach destroyed. Sept 7 1866. Memorial erected by East Oregon Pioneers.

Just before lunch I’d descended from the high pass of the Ochoco Mountains down down down into the town. Racing down the canyon side, I knew that the land’s revenge was coming at me later (especially since I look at a climbing profile of the ride I’m taking each day.) However, it’s always been difficult for me to imagine a worse sensation when in the arms of a better one, so the fact that I’d actually have to climb this hill’s evil twin was a mere abstraction as I whizzed down from the high pass of the Ochocos.

Of course I’d had to climb that pass too. Yes, there were two long climbs today. Departing Prineville, I ascended gradually over a 20 mile grade through the Ochoco National Forest up the side of the mountain range of the same name (for those counting that’s 2 mountain ranges down out of 4 on this trip — not bad!) The climb was long and steady, but aside from a little bit of a headwind at first, it wasn’t that bad. The odd thing about the climb was the smell — for much of the way I could smell nothing but death. While roadkill is a cyclist’s ever-present companion in wild areas, I have to say that today was way over the top. An incomplete census of animals (dead and quick) observed today: deer (dead, many), turkey (alive, one, seemed lost), skunk and raccoon (dead, countless), rattlesnake (live, one eek!), grouse (I think, live, a gaggle), cattle (live, many many.)

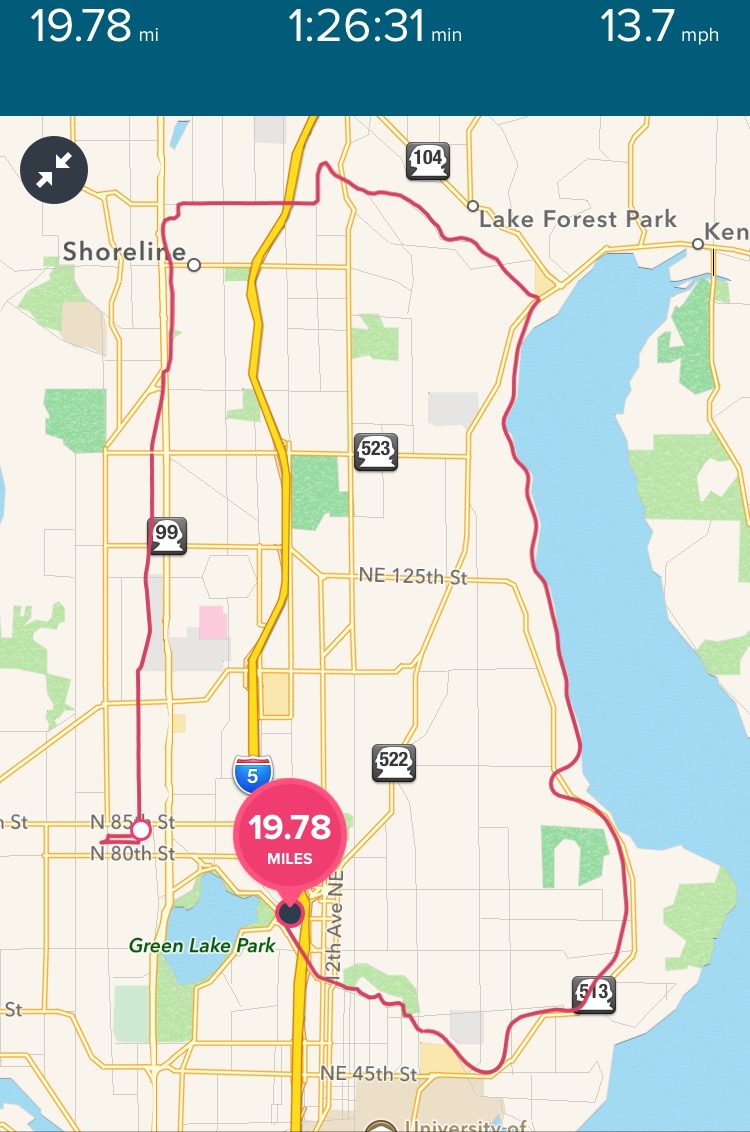

it’s time for bed now, after one of the tougher days on this trip. Eighty-nine miles, over 5200 feet of climbing. Tomorrow is a light day of only about 35 miles. I plan to do most of it early and to use the day to check in with work and then rendezvous with the folks from Prairie City. I’ll be glad for the (relative) rest.