I was back in the saddle today after a day off in the enclave of Lava Hot Springs, Idaho (population ~400.) I can’t recommend this place and its perfectly crystalline hot pools enough. Go there! If you do, you’ll also understand where all of the hippies in south eastern Idaho went — those that didn’t leave entirely.

The ride out of town and back down into the broad valley of the Pontneuf river was a joy — I was rolling swiftly and made great time in the morning under a non-threatening cloudy sky that more than anything kept the harsh sun away. It was an amusement to watch the shifting patterns of clouds above me; now dark, now lighter, now entirely blue. What part of the shift was due to the clouds, and what was due to me, inching my way along at a respectable 14.5 mph? Aside from a few temporary headwinds, I made great time, and was soon pointed directly south at Preston, Idaho, a scrubby town less than ten miles from the Utah line (and, incidentally, the setting for the movie Napoleon Dynamite.) So I knew where I was going … but what I wasn’t prepared for the drama and tragedy the next sixty miles of this valley would reveal.

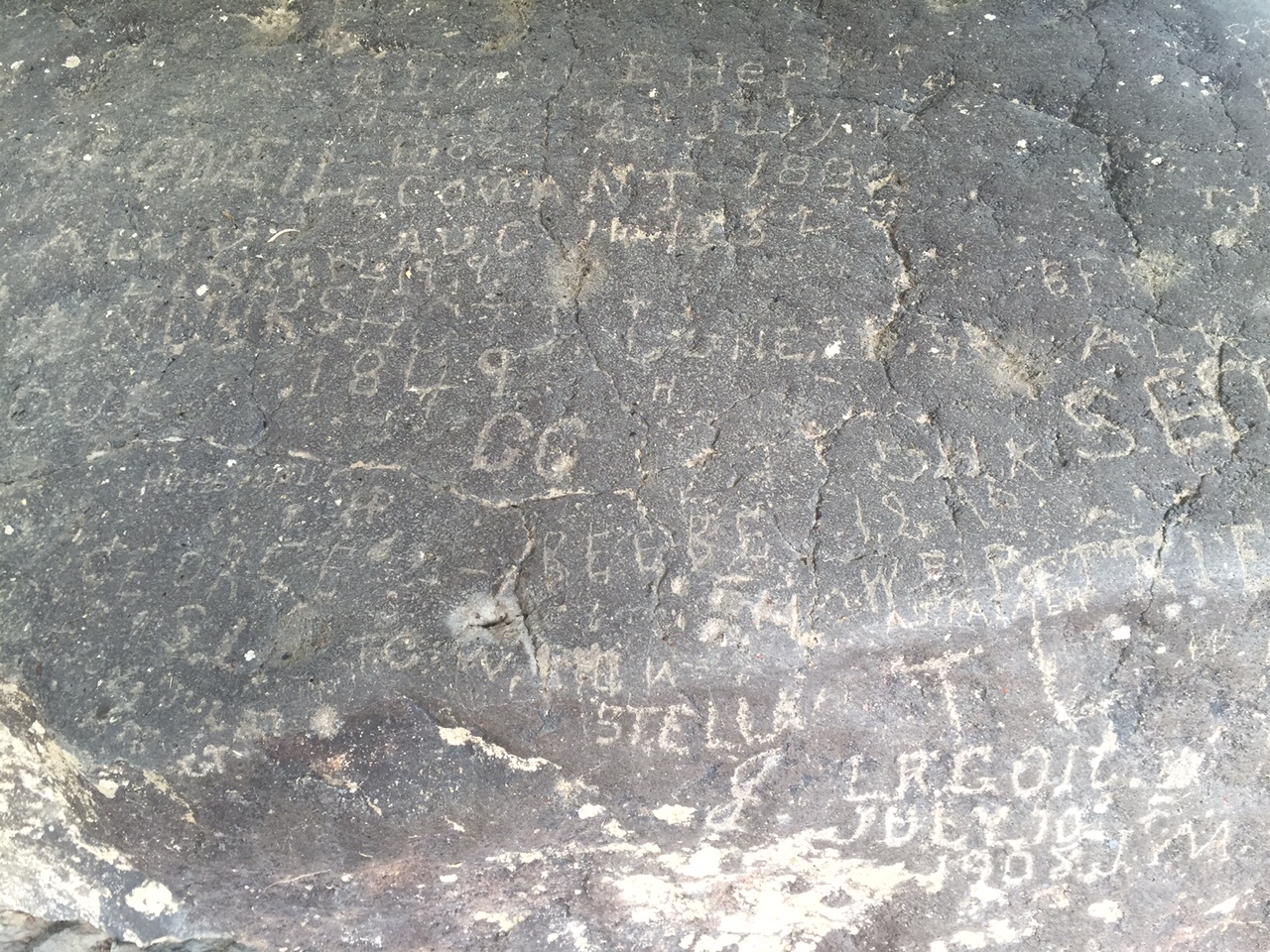

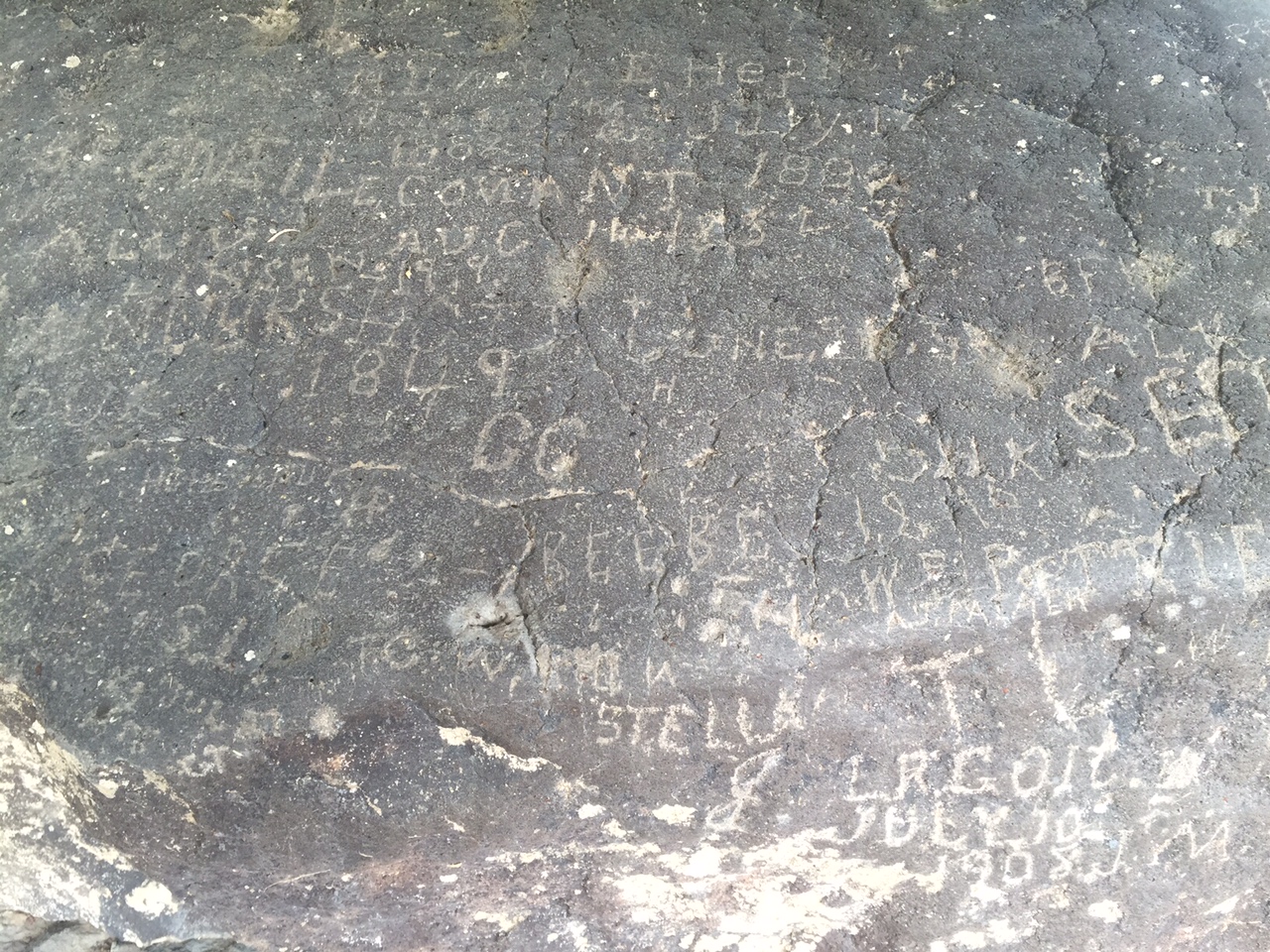

From the north, you can’t see Red Rock until your almost on top of it. It’s a pockmarked, gnarly looking butte to the right of US91, a mere point of minor geological interest, I thought, until I reached a small installation with some geological information from the always-helpful Idaho Historical Society. What I learned from their rustic sign was that this rock formation and the gap in which it sits was the outlet to a vast inland lake — a sea almost — which extended from this point in the north down the broad valley in front of me through the Salt Lake basin and all the way down far far into Nevada. In fact, the current Great Salt Lake (shrinking still) is but a remnant of this truly massive body of water which dominated the entire region until about 8,000 years ago when it began to recede and disappear due to a drying of the climate. Right under Red Rock flowed a rushing river with the volume of the Amazon which helped to drain the lake. Eventually it drained it totally — and the lakebed was now a desert, or a marsh, or in places a pasture. But scanning to the south, I could almost see its ancient contours marked on the hills and mountains all around — a broad, flat-bottomed valley which was the lake’s old bottom. And the high mountains, re-encroaching on my journey for the first time in a week — these would have been made islands or isthmuses by the expansive waters.

In deep time, no one owns the earth. It sweeps away the living and the dead. Seas rise and fall, climates change, entire ecosystems collapse or are birthed. This is a source of fascination for me, and of comfort. Because it seems so often that in the short term we do our best to dominate the land, to steal it and its products and to water our crops with the blood of other people. And so it was in this valley.

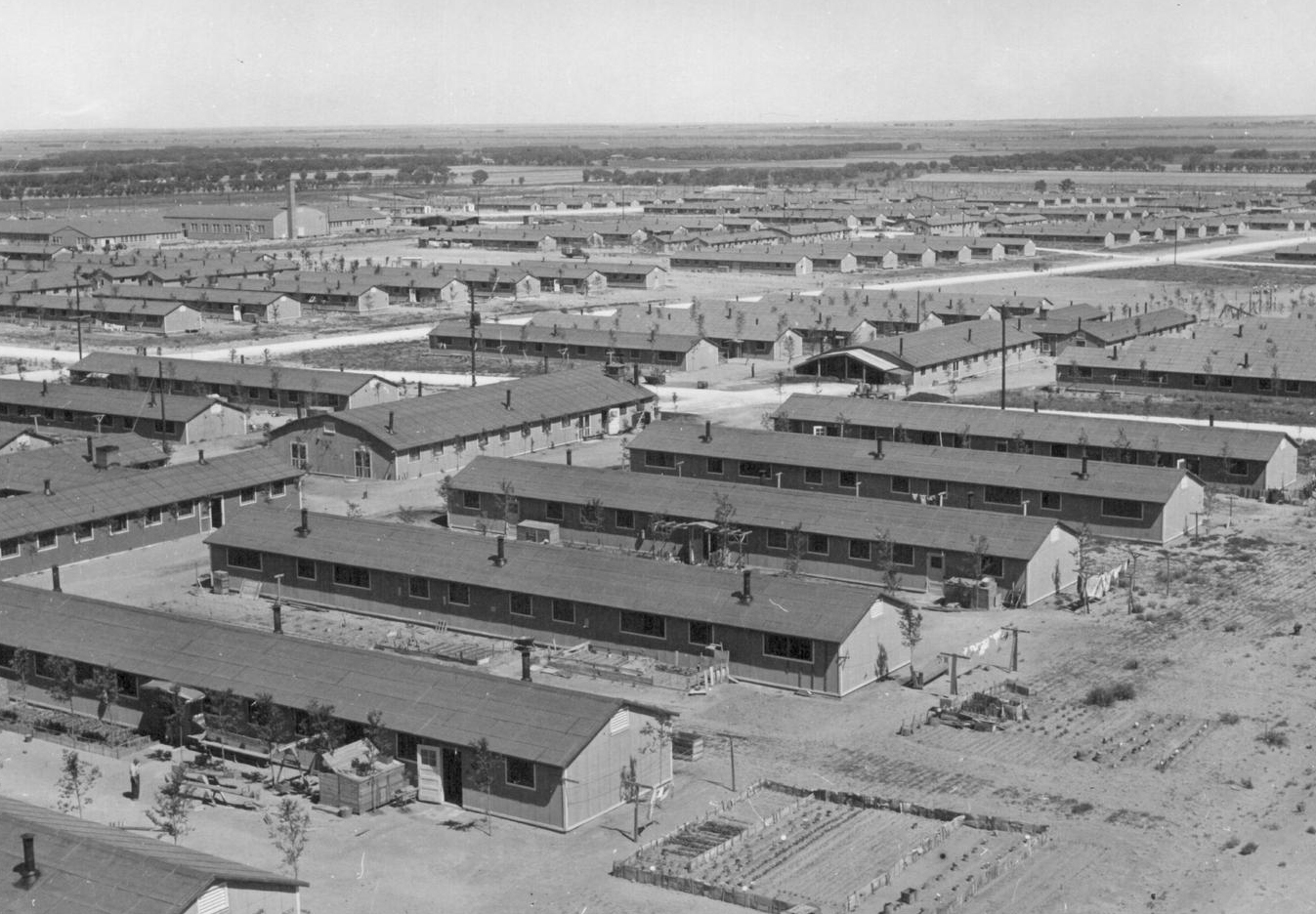

The first to inhabit the old lake-bottom were the western Shoshone people. This was their traditional hunting ground, used for thousands of years in as part of their annual hunting and gathering cycle. The next were the Mormons under Brigham Young, who by that time had established Salt Lake City and whose settlers had pushed up the Cache valley into this area. Then came other American pioneers — those who followed the Oregon and California trails and either homesteaded or exploited this land on their way through, and also gold miners who used the valley as a road and source of food. The land was getting crowded. The Mormons and other settlers began taking so much game (buffalo, elk, animals for fur) and land for cultivation that the Shoshone became impoverished and starved and were reduced to begging and sometimes stealing food from the newcomers. There were conflicts — real and invented, between all parties. The Mormons fought the US Government (there was a brief war even.) The Mormons then tricked and fought the Shoshone. The Shoshone, possessed of a keen sense of blood revenge, killed in the measure that they themselves were killed. The Mormons encouraged the Shoshone to steal from US wagon trains, and when they did the US responded without mercy. In the midst of the civil war Lincoln dispatched soldiers from California to crush the Shoshone’s non-existent “rebellion.” In January 1863, their main camp on the shores of the Bear River was attacked and harshly destroyed. Over 400 men, women and children were butchered and raped in the most ruthless fashion and their dwellings destroyed.

As I descended towards the bottom of the valley of the Bear, there were memorials from all sides. Native Americans commemorated the massacre by tying ribbons, yarn and other objects to certain trees. These flapped quietly and colorfully in the light breeze. Typically, we Americans erected a threatening-looking obelisk complete with shameful inscription: Erected 1932: the battle of Bear River was fought in this vicinity January 29 1863. Col. RE Connor, leading the 300 California Volunteers from Camp Douglas, Utah against Bannock and Shoshone Indians guilty of hostile attacks on emigrants and settlers engaged about 400 indians of whom 250 or 300 were killed or incapacitated including about 80 combatant women and children. 14 soldiers were killed, 4 officers and 48 wounded of whom 1 officer and 7 men died later. 72 were severely frozen. Chiefs Bear Hunter, Saowitch and Lehi were reportedly killed. 175 horses and much stolen property were recovered. 70 lodges were burned.

70 lodges burned. 80 “combatant” women and children. 250 or 300 killed (it was actually over 400.) In a way, it was a strange relief to see it all spelled out and counted like that, our government’s old and enduring cruelty to the original inhabitants of the land. Knowing exactly what happened, even if it’s presented in a twisted and near-celebratory context like this one, is at least in some way better than forgetting. I pedaled on, unable to think of anything else. I hope that monument stands for a long time and reminds us of what we as a country did at Bear River, and at so many other places across the west — of the cruelty and blood on which our mythical west is built, and on which we live and walk every day.

As the old lake-bed widened, I entered the state of Utah — center of American Mormonism. For some days, there’d been an LDS church in just about every little town I’d rolled through (Mormons are populous in southern Idaho too.) But now, the church was absolutely everywhere. Every single subdivision in Logan clustered around the spire of a Mormon church. Every single farming town had one too. I could see the grand temple of Logan from over 7 miles away, its twin spires pointing at the sky as if to say “Up there! Look away from this old lake bottom where so much blood has been spilled. Look at the sky and wonder about the clouds and ride your bicycle and don’t worry about it.”

It didn’t work. At the end of 81 miles I was still troubled by what I’d seen and learned. So I went to see a movie — the Martian, in which Matt Damon plays an astronaut trapped alone on Mars … a planet with no massacres, wars or nations. At least not yet.