Today was a day of roughly following the Snake river, and I84 (but neither too closely) as they both plunged headlong east. In about 50 more miles the river, but not the freeway, bends north toward its origin in the Tetons and Yellowstone National Park, but for now it heads directly east, through a gap between the low mountains of central Idaho to my north and the growing hills to my south. Today was also a day of vast fields of potatoes and sugar beets, of corn and hay and of farmers in huge vehicles working to get the crops in. The river feeds the land around here through a network of irrigation channels, many of which I crossed on little bridges on the secondary roads I took from Bliss down to Jerome, Idaho, north of Twin Falls. I decided to skirt this small city rather than enter it, and stayed deep in the farmland nearly all day, picking my way through the little agricultural towns that used to support the farming communities around them.

Many of these little towns are shells of their former selves — depressed little places with boarded-up buildings and only a few functional businesses and churches and perhaps a school or two. Farm families are more mobile than they used to be, and can drive the extra 15 minutes on the freeway to get to a WalMart or a chain supermarket rather than rely on the businesses that their forbearers likely patronized every day. Of course this change isn’t unique to this part of Idaho, but today I felt like I noticed it with particular sharpness as the haul of crops was brought in from the beet and potato fields all around me. At the same time, the only food on sale in any store was processed, packaged, or (maybe) fried — and all shipped in from far away. There was poverty too — the pretty obvious kind. Federal programs providing nutrition to pregnant women were advertised in every store window while Fox news blared loudly in the background. At one point a woman in her seventies with strange growths on both of her arms approached me as I was resting and asked me to help her son move a large couch. We moved it, he and I, into a falling-down house. His two daughters watched.

There’s something about rural America that blurs the lines of reality and fantasy and makes me doubt for just a second that there isn’t something … untoward … going on beneath the surface. At one point I turned a corner and was confronted by the biggest junkyard I’d ever seen — if a junkyard it even was. Dead cars, trucks, some of them very very old, stretched nearly to the limits of my sight. It was as if an entire section of someone’s farm had been surrendered to them and become a massive automotive graveyard. Maybe this air of unreality has to do with the fact that so many people here (and elsewhere in red America) believe, in quite a matter-of-fact way, certain things that are for me difficult to even imagine. “What is happening in our world lately?” demanded a placard at one gas station picturing a blood-red sunset with threatening clouds. “Join us Wednesday nights at Valley Christian Center, 35 Main Street Hazelton at 6pm, to find out. We will be taking a walk through the book of revelation with the series Agents of the Apocalypse”

If the world is going to end, then what isn’t possible?

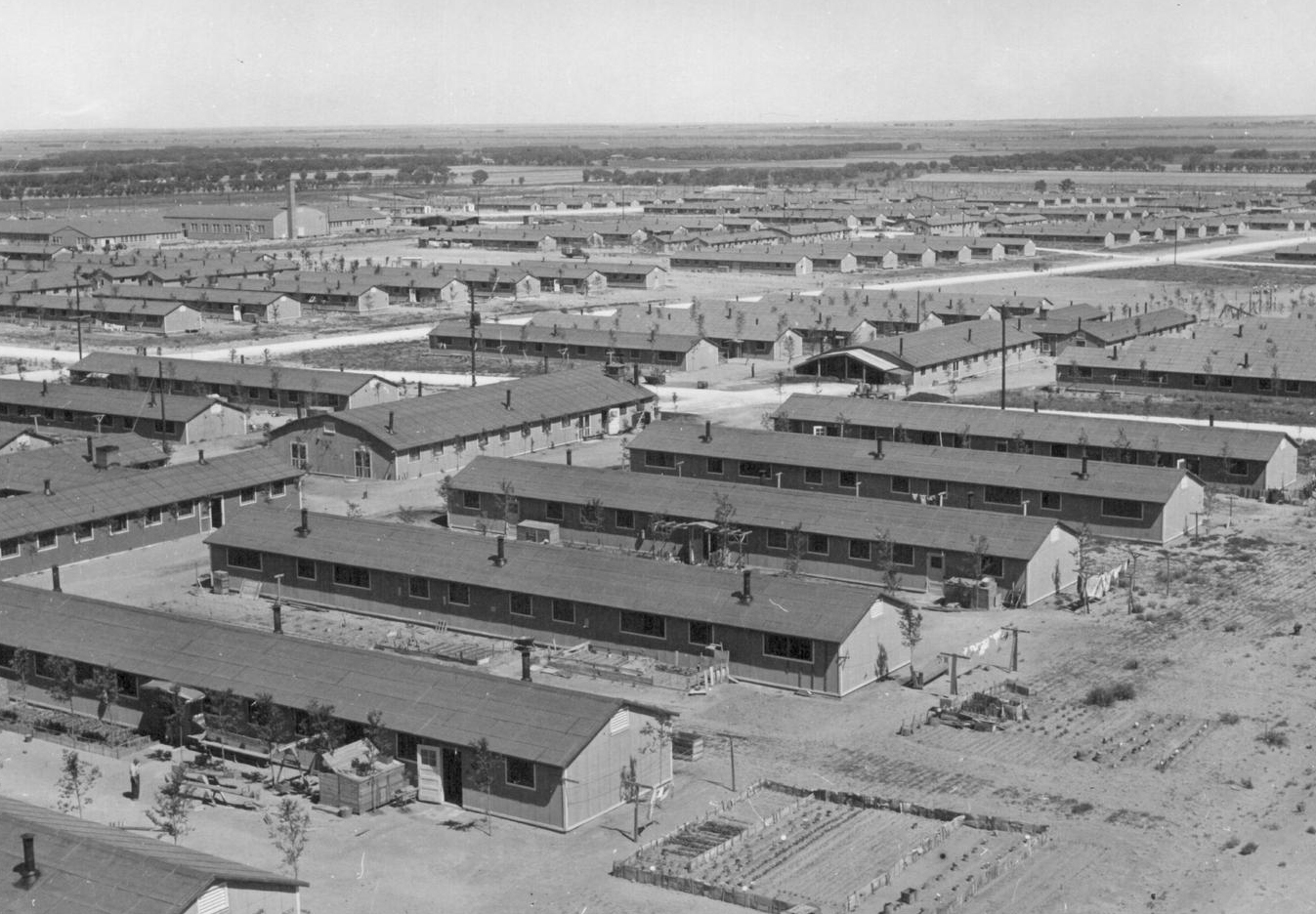

I’ve always thought that many Americans are possessed of a poor sense of when to pay attention to the past and when to look to the future. We quote the founding fathers when it suits us, but forget them as soon as it doesn’t. We commit obscene acts of genocide and crimes on a massive scale, and then forget that they ever happened. Half of us (or something) believe a supernatural apocalypse is coming, but we refuse to foresee the natural one we’re creating with our cars, coal plants and airplanes. I arrived at the turn-off for Hunt, Idaho at about 2pm under a hot sun. Hunt was the location of a concentration camp during the second world war which imprisoned over 9,000 entirely innocent American citizens of Japanese descent. The US government forced the sale of their property and businesses and then removed these Americans to places like this in the high desert for the duration of the conflict.

At the turnoff, a sign read: Excluded from their west coast homes by military authorities, over 9,000 Japanese Americans occupied Hunt Relocation camp 4 miles north of here between 1942 and 1945. Until they could resettle to other places, they lived in wartime tarpaper barracks in a dusty desert where they helped meet a local farm labor crisis, planting and harvesting crops. Finally, a 1945 Supreme Court decision held that United States citizens could no longer be held that way and their camp became Idaho’s largest ghost town. This sign (provided by the Idaho Historical Society) and its softball gloss of history are so offensively terrible that I won’t comment on them here, but the whole scene seemed only to add to the air of unreality — of denial and fantasy — that permeated this countryside.

Maybe I’ve been thinking dark and deep thoughts today because my rear end is really killing me — just a theory. Seven hours in the saddle is a lot, and I’ll be glad for another day off on Thursday, and a short day Wednesday. But as I drew close to Burley, my home for the night, I started pondering tomorrow and its challenges. It’ll be another longish one — today was 80 miles, tomorrow will be a few more even. And the route is a bit uncertain — all roads except I84 itself more or less fail about 50 miles to the east of here as the Snake enters a bit of a canyon, and it looks like I’ll be back on the freeway shoulder for about 6 miles tomorrow afternoon. But the day will end in Pocatello which is a pleasant-seeming college town. The day after tomorrow I will turn south and make for Utah and the end of the this voyage … assuming the apocalypse doesn’t happen first.