Note: this post is a little bit about cycling, and a lot about war, history and my extended family. You never know where a bicycle will take you, and this is where mine took me on this particular day. Back to more bike-centric posts soon, I promise, but in the meantime, I hope this is interesting to some.

Today I set out from the town of Épernay, France with the objective of riding to a military cemetery. Such a destination is a first in my cycling life so far — I’ve passed by many graveyards on two wheels, even stopped to look. But one has never been my destination, until today.

In the United States, particularly in rural places, the graveyard is typically on a hill on the outskirts of town. I was always told this was to prevent unpleasant post-burial disasters involving flooding — floating or water-logged caskets and the like. Here in Europe, the old burial places huddle around churches, sometimes exceedingly close or even within the buildings themselves, as if the bodies were jockeying for position. Military cemeteries seem different, more like parks. The only one I’d actually seen in person before was the huge, famous one at Arlington, Virginia. My maternal grandparents took me and my brother there when I was 10. I remember the ranks and ranks of graves, the tomb of the unknown soldier, Kennedy’s tomb.

But my particular destination today was the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery some 27 miles from Épernay, near the town of Fère-en-Tardenois. There lies buried a distant relative of mine who died in the First World War: a Private Rhen Hilkert of the American Army’s 28th Infantry Division. He was my great-grandfather’s brother, or my maternal grandmother’s uncle (though he was already dead more than a year by the time she was born.) Rhen was 28 when he died, thousands of miles from his home in Indiana.

As my bicycle rolled out of town early this morning, I was mostly thinking about why I chose to make this trip. No one had necessarily asked me to, although when I mentioned it my mother had been quite enthusiastic about the idea, and had helped out by sending various links and thoughts by email. Nor was I the first member of the extended family to visit this place. In the early 1930s, my great-great grandmother, a woman named Olive, had visited the Tardenois as part of a government program that allowed mothers to see their war-dead sons’ overseas graves. I tried to imagine her voyage by ocean-liner and then train to this part of France which no doubt still bore many of the signs of war. And then another relative, an enterprising cousin of ours named David, had been to the cemetery some years ago and taken photos of the grave, which can now be found online. In the end I settled on the idea that it would have been odd for me not to visit this place … being that I’m in this part of the France, and have a few days to bicycle anywhere that I want.

Between the Tardenois plain and Épernay are two defining geographic features: the Fôret de la Montange de Reims which is a massive wooded bluff, and down in the valley it overlooks, the river Marne, a tributary of the famous Seine. I clunked off the road on my tank of a French bicycle and started down the pavement of a beautiful bike path which followed that river and its various side-canals for some 40km in this region. To my right was the slope of the montange, the first couple of kilometers of which were actually not forested at all but covered by ranks and ranks of vineyards, all producing grapes for the worlds’ champagne. I passed through little riverside villages and could see others up in the heights. All day, in fact, I rolled through these sorts of little places — tiny postcard-like villages with largely unpronounceable names, sheltered in the land or cradled by riverbends and always centered around a little church.

The Marne itself was green and lazy. Weeds and fish were visible in its depths as I rode by. Even before eight in the morning the day had turned hot. France was experiencing an unseasonable heatwave, with June temperatures to exceed 93 degrees. I grimaced at the climbing to come.

One little riverside town had dedicated its outskirts entirely to caravaners. RV-camping seems to be popular around here. Unlike in North America, where such vehicles largely confine themselves to scenic campsites, state parks and the like (the exception being the horrors that are WalMart parking lots), folks here seem quite willing to camp out in various not-particularly-lovely places: wide areas of the road, dusty industrial riversides, plots of grass near motorways. I pedaled very close to some of these RVs, so close that I worried I would run over anyone stumbling out the door of one. At one point I watched an enterprising French man in his seventies dressed in boxer shorts and a tank top cast his fishing line into the Marne while simultaneously brushing his teeth on the veranda of his caravan. He was observed from the river by a family of obese swans, who I suspect he was feeding.

At the village of Rueil, I left the riverside and climbed up the side of the mountain through the hill town of Châtillon-sur-Marne. The climb was pretty intense, but mostly this was due to the increasing heat and the great mass of my bicycle, which I think could be used to plow snow in the winter. I pushed up … 5 minutes of climbing, 10, 15, on toward the centre-ville, distracting myself as I always do on climbs with audio entertainment. Being a distractible person works much to my detriment in many settings, but does me a great service when powering through any kind of unpleasant physical activity. In this case I switched on the continuation of the audio version of David Sedaris’ new book (his journals — hilarious.) And so I laughed and sweated, up through the steep town and past its grand promontory.

At that point, many hundred feet over the river, stood a massive statue of a pope — I forget exactly which one (maybe one of the Urbans?) The statue didn’t appear to be particularly well made, but compensated through its sheer bulk, so that the pontiff kind of loomed over everything in the area — parish church included. His position seemed somewhat at odds with the orientation of the town, as if he addressed something well beyond it. The valley? Rome? Jerusalem? His arm is raised in what I guess is a benediction, but to me he looked uncomfortable and even cross, like an overdressed traveller who had just missed the last bus back to Italy and is trying, despite his vestments, to flag it down. I pushed on, ascending above his holy crown and passed into the shaded forest, soaked with sweat.

In doing so I had crossed an important boundary. In WWI, the Germans had failed to get their hands on any of the lands through which I’d just passed. But to the northwest of my position, beginning roughly with these woods and extending for some 40 miles to the town of Soissons, they had in the spring of 1918 rampaged over the entire plain of Tardenois, pushing the French, and their American and British allies, back beyond the Marne and to within 65 miles or so of Paris itself. Behind them they dragged all sorts of unpleasantness: towns in this region became massive ammo dumps, fields were cleared to serve as bases for the new bi-planes. A super-gun with a range of over 70 miles was transported by rail in order to fling enormous explosive shells all the way to the eastern districts of Paris. The Second Battle of the Marne was the name given to the terrible struggle to take this chunk of land back. It was this battle that cost Rhen Hilkert his life.

Soon I emerged from the trees onto the Tardenois plain itself. Here the vineyards of the valley were replaced by fields of wheat, corn and beets in all directions, with scattered woods and towns. For a plain, there sure seemed to be a lot of hills. One massive ravine stood out, just after the town of Antheny where the road treated me to a thrilling downhill and a somewhat less welcome climb back out. Allied armies, I’d read, sought protection in these little valleys, finding their wooded bottoms good for concealment from aircraft and machine guns. But the Germans (and Allies too it should be mentioned) also had poison gas at their disposal, which being heavier than air clung to the bottom of these gullies and caused mass death.

We don’t know exactly how Rhen Hilkert died, but here’s what is known: in the middle and end of July 1918, the allies stormed into the land through which I now rode to force the Germans back. Though the German army had taken over the Tardenois swiftly and powerfully, they’d done so at the cost of overextension. So when the French, Americans and British counter-attacked, the Germans had no choice but to fall back. In the process they extracted a great cost. Many villages in this area were wiped completely off the map — so damaged by shelling or intentional destruction that they were never rebuilt, their residents dead or scattered. It is recorded that the Germans would retreat back a mile or so, and then set up line after line of hidden machine guns and traps. The guns were often concealed ingeniously in ruins or high crops or woods, positioned to tear to shreds advancing groups of soldiers on lower ground. As I biked by, I could see all of the terrible places these weapons could have been positioned. Danger would have been everywhere. There were also mines, and almost continual exchanges of artillery fire and gas. German planes, superior to the allied ones, ruled the skies. All of this continued for weeks and weeks, until at last the Germans had been pushed back to the river Vesle, thus liberating much of the Tardenois.

It should have stopped there. But in subsequent days, orders came down from on high that the US 26th division was to cross the Vesle to the little town of Fismette, across the small water from the town of Fismes, which the Americans had occupied at great cost. The Germans for their part occupied the heights above the village, which gave them an impenetrable perch from which to rain down ordinance on Fismes and Fismette. When parts of the 26th division were nearly wiped out in a single day of fighting (August 8, 1918) the 28th division was ordered to relieve them, a manoeuvre that apparently had to happen in the dead of night to avoid slaughter from above.

At this time, Rhen Hikert would have been with his 28th division in either Fismes or Fismette, in the midst of terrible carnage. We know that on August 9th, the American attack was ordered to be renewed, and that the Germans counter-attacked several times. By that evening of the 9th, the surviving Americans in Fismette were huddled in a few basements in the town, running out of ammunition under continual bombardment by phosphorus, high explosives, flame-throwers and gas. One survivor described watching soldiers burn “like leaves”. The path from Fismette to the allied bunker in Fismes was apparently not hard to follow, since it was marked by a trail of dead couriers. By dawn on the 10th, one way or another, Rhen Hilkert was dead.

This story and much else was explained to me at the cemetery, where I had finally arrived, by A, a lovely French woman who worked as an interpreter and guide at the monument. Despite my sweaty, buggy appearance, she greeted me warmly in English and said she loved that I’d ridden all the way from the valley. Her son, she told me, lived in London and had “a passion for the bicycles.”

She and I walked up the manicured lanes of the cemetery in search of Rhen’s grave. Row upon row of crosses — some stars of David. The place was immaculate, the pathways so clean you could eat off of them. The number of crosses was overwhelming — so many that they appeared like a mass on the landscape. And there it was, plot C, row 35, grave 16. She took some photos of me standing next to the big marble cross with his name on it, and then let me stay alone for a while. After staying with Rhen for a few minutes and finally giving his cross a little pat (I wasn’t sure of the protocol) I walked up and down row 35. What shocked me the most was the number of men who were never identified. Instead of names, their graves read Here Rests in Honored Glory an American Soldier Known But to God. There were a lot of these — the next eight or nine down the line from Rhen were all so marked. I thought of Olive, and how she was lucky to have had a particular grave to visit — that there had been enough of a body left to identify.

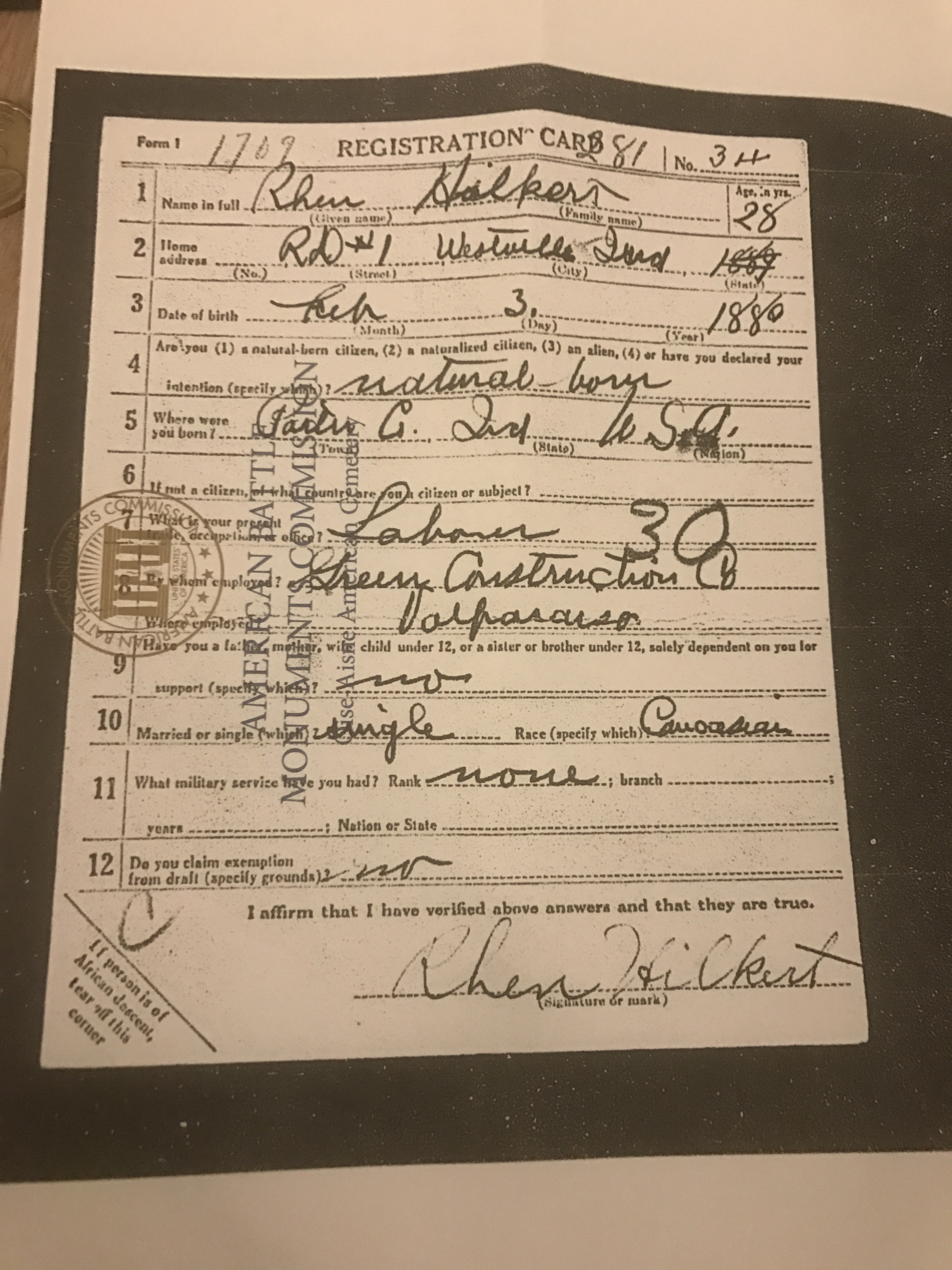

Back at the cemetery office, A informed me that Rhen’s body would have been moved here from a temporary cemetery closer to the battlefield on which he died. This would have happened sometime in 1919. At that time, Rhen’s parents (Olive and Isaac) would have had the choice of whether to repatriate his body or allow him to rest here. I wonder why they chose the second option? She also produced a photocopy of his draft card, which I found particularly interesting. Rhen had been 28 when he enlisted, though due to an apparent arithmetic error, the army clerk had listed his birth year as 1880, which would have made him a decade older. He was single, with no dependents, and listed himself as employed as a laborer at the Green Construction Company of Valparaiso, Indiana. He lived in Westville, Indiana, a tiny town both then and now. His eyes were blue, his hair dark, with medium height and build, said the form. So many questions.

A and I were joined by her boss, a Mr. D — a small, sturdy American fellow with a hawk-like nose in his mid 60s. Mr. D’s tattoos indicated that he was ex-military. He was nice enough, really quite welcoming, though I didn’t like the frequency with which he interrupted A. The three of us talked for a little while about history and the war, and then about Mr. D’s travels to various military bases in the United States. He spoke of them rather as if they were theme parks. He’d been to Fort Lewis near Seattle, which he mentioned when he heard where I was from. I think he was waiting for me to say I was a veteran or had some military connection, and may have been a bit disappointed when such news wasn’t forthcoming — don’t ask, don’t tell I guess. I took my leave, thanking them both for being there and helping me out — I really meant it too.

As I rode away, I tried to imagine A and Mr. D’s working life there together, sitting all day in the small office, or patrolling the grounds together supervising the garden workers from their golf cart. What did they talk about when there were no visitors like me? In winter, for instance, it must be just the two of them out there in the fields, alone among the dead.

I cycled back to Épernay with only brief stops for water. It was well above 90. Back over the plains, the ravines, and into the woods. I thought a bit more about Rhen and his short life. Had he he enjoyed working on the farm, or at the Green Construction Company in Valpo? How did he feel when he signed that conscription form? Why didn’t he correct the clerk’s obvious errors? This made me wonder if he was a passive, compliant kind of person — not the sort to question authority. But surely there was more to his personality — I found myself wishing I could have asked him even more questions. What were his dreams? Did he want to get married? Was he even the marrying type? Did any part of him see the idea of going overseas to war as an adventure?

I flew down the hill towards the Marne. If that’s how he’d felt, I wished he could have found adventure in any kind of better way. Not that he’d had the choice. His conscription card showed that Rhen enlisted at the end of March and was dead before mid-August. He barely had time to adjust to what was happening to him, as the gears of the US military processed him. Armies are machines that ingest poor and working people and spit out compliant soldiers and dead bodies — or so it’s always seemed to me.

Rhen’s brother John fought in the Marne too — a mere 40 miles away near Soissons. John’s army hid in a large forest for weeks and then burst out from under its eaves to attack the German flank (or so I read.) John would survive the war but return to Indiana with severe shell-shock, or what we’d now call PTSD. My maternal grandmother remembered him well — a ruined man, someone she pitied. John died in 1930, still young, not long before Olive set sail for France.

By 1931, Olive Hikert had buried her husband and two of her four boys in the past twelve years. In fact, she would survive all of her sons, save one: my great grandfather Mayne, who may have avoided conscription himself because of his young son Ralph and his wife Ruth. Mayne joined the railroad and moved to the city, where my grandmother was born. She, like her own grandmother Olive, would wait as the men left for war yet again — for her it was a husband who shipped out to the Pacific and made it back.

It was those two — my maternal grandparents — who had showed me around Arlington Cemetery when I was ten. Thinking back to that day in the eighties, I remember clearly the feeling of holding my grandmother’s fantastically manicured hand as we walked through the park up the hill to John F. Kennedy’s tomb — the one with the eternal flame. I also remember as a fifth grader being skeptical that it was in fact eternal. I’d apparently already figured out that nothing really was.

My grandma was quiet that day, largely delegating the wrangling of my little brother to my my grandpa, who kept having to retrieve him from various off-limits areas. I imagine she was thinking of war, and what it does to families and mothers. Maybe too she thought of her own grandmother Olive, and of the fields through which I’d just travelled — the place her uncles had come to die.